An Ethiopian cup in rhinoceros horn (2/2)

The first part of this article is available here.

The different species of Rhinoceros

The rhinoceroses (Fig. 9) belong to the family Rhinocerotidae (Gray, 1821) and form a group of four genera and five living species. The following genera are described: Ceratotherium, Dicerorhinus, Diceros and Rhinoceros.

Two of these genera are native to Africa: Ceratotherium simum (Burchell, 1817) and Diceros bicornis (Linnaeus, 1758). The other two are from South Asia: Dicerorhinus sumatrensis (Fischer, 1814), Rhinoceros sondaicus (Desmarest, 1822) and unicornis (Linnaeus, 1758), the latter two forming a combined entity of two species.

Apart from their more or less massive morphology, the main visible characteristic of rhinoceroses is their horn(s). The two African species and the South Asian Dicerorhinus sumatrensis have two horns, while the South Asian Rhinoceros unicornis and Sondaicus have a single horn. The front horn develops on the nose while the rear horn (if present) develops on the front of the skull.

Rhinoceros and conservation – The IUCN Red List

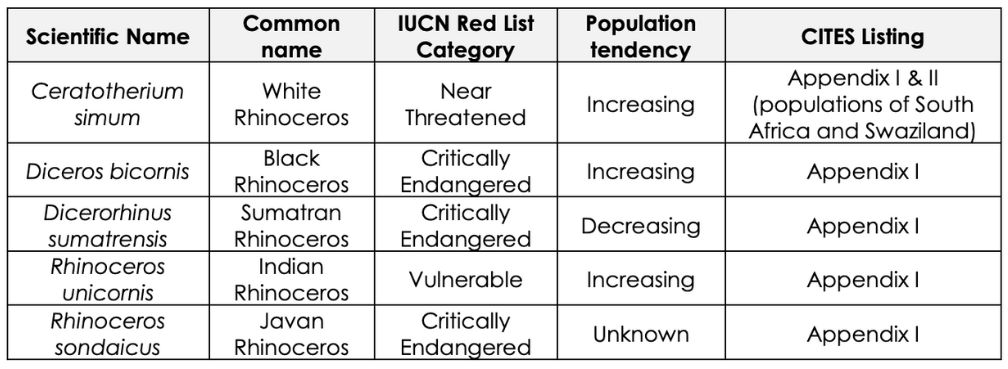

The IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Red List identifies three species as Critically Endangered (Fig. 10).

- Diceros bicornis (Linnaeus, 1758)

The species Diceros bicornis (black rhinoceros) has been listed as Critically Endangered because the population has declined by about 97.6%, mainly due to poaching. Since 1995, the number of black rhinos has been steadily increasing. Its population doubled to 4,880 at the end of 2010. Currently, there are still 90% fewer than three generations ago. - Dicerorhinus sumatrensis (G. Fischer, 1814)

This species of Dicerorhinus sumatrensis (Sumatran rhinoceros) is classified as Critically Endangered due to its very serious decline of over 80% over three generations. The population size is estimated at less than 250 mature individuals and a continued decline of at least 25% is expected within one generation. - Rhinoceros sondaicus(Desmarest, 1822)

The species Rhinoceros sondaicus (Javanese rhinoceros) is classified as Critically Endangered because there are less than 50 mature individuals. It is in continuous decline.

Rhino horns and trade – CITES

CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) is a multilateral treaty to protect endangered plants and animals. It is also known as the Washington Convention.

Its aim is to ensure that international trade in specimens does not threaten the survival of the species in the wild. Appendices I, II and III of CITES are lists of species that are given different degrees of protection to prevent over-exploitation. The species considered most threatened are listed in Appendix I of this convention.

All rhino species, with the exception of the Ceratotherium simum simum (White Rhino) populations of South Africa and Swaziland, are listed in Appendix I of CITES (Fig. 10). This does not mean that trade is prohibited, but that the market is regulated by a strict directive.

Today in Europe, only artisanal horns manufactured before 1 March 1947 and imported into the EU before 1 July 1975 for Ceratotherium simum and 4 February 1977 for the other species (Diceros bicornis, Dicerorhinus sumatrensis, Rhinoceros unicornis and Rhinoceros sondaicus) may be sold without administrative authorisation, provided that they are accompanied by a recognised expert opinion certifying the date of manufacture or at least if the manufacture is clearly prior to the deadline mentioned.

Trade in horns, whether or not they are handcrafted, imported into the European Union after 1975 or 1977, depending on the species, is prohibited. Export from the European territory is subject to a licensing process which is only issued for very specific operations, such as museum exchanges or scientific research.

Conclusion

It is sometimes the study of ethnographic documents that allows gemologists to place objects in their context. Here, the rhinoceros horn cup has allowed us to study its historical use, its identification and to focus on the protection of the species.

Of course, if gemmological laboratories are now able to analyse and certify antique rhino horn pieces, they have a moral duty to ensure that these pieces are genuine antiques and, where appropriate, to report to the relevant authorities cases falling under the prohibitions mentioned in CITES.

authors

- Candice Caplan is an archaeo-gemmologist at the GGTL Laboratories in Geneva. She became interested in gemstones during her studies of Egyptology, as carnelian, the symbol of life, was used extensively in ancient Egypt. Since then, she has been studying ancient jewellery and gems from all periods and all origins, such as the treasure of the abbey of Saint-Maurice d’Agaune (Valais) dating from the early Middle Ages. But laboratory research on perfectly contemporary problems is also part of her activity, whether it concerns the treatment of gems, the origin of the colour of green diamonds or the most recent synthetic stones. ResearchGate, LinkedIn.

- Emilie Disner has been a gemologist at GGTL Laboratories in Geneva since 2012. She first specialised in emeralds, dealing with epoxy resin cleaning and oiling of these stones as well as working on geographical origin, fillers and the importance of enhancement. She now works as Operations Manager in the laboratory. A keen traveller, she has had the opportunity to visit the mines in Muzo, Colombia, Luc Yen in Vietnam, Pailin in Cambodia, Chanthaburi in Thailand and Ratnapura in Sri Lanka. She was also able to visit the pearl farms in the beautiful Halong Bay in Vietnam. She is now working in digital communication for jewelry brands. Website, ResearchGate, LinkedIn

References

- Blainville, H. M. D. D. (1817). Lettre de MWJ Burchell sur une nouvelle espèce de rhinocéros, et observations sur les différentes espèces de ce genre. Journal de Physique, de Chimie et d’Histoire Naturelle, 85, 163-168.

- Chapman J. (1999). The Art of Rhinoceros Horn Carving in China, Christie’s Books.

- Desmarest A. G. (1820-1822). Mammalogie ou description des espèces de mammifères. Première partie contenant les ordres des Bimanes, des Quadrumanes et des Carnassiers. Seconde partie contenant les ordres des Rongeurs, des Edentés, des Pachydermes, des Ruminans (sic) et des Cétacés. Ed. Mme Veuve Agasse, Paris, 2 vol. (VIII + VIII), 555 p.

- Fischer G. (1814). Zoognosia tabulis synopticis illustrata. Volumen Tertium. Quadrupedum reliquorum, Cetorum et Monotrymatum descriptionen contiinens. Mosquae: Nicolai Sergeidis Vsevolozsky, 3.

Guindeuil, T. (2014). - Gray, J.E. (1821). On the natural arrangement of vertebrose animals. London Medical Repository 15, 1821 April 1: 297-310.

Hieronymus T. L., Witmer L. M. and Ridgely R. C. (2006). Structure of white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum) horn investigated by x-ray computed tomography and histology with implication for growth and external form. Journal of Morphology 267(10)1172–1176. - Linnæi Caroli ó. (1758). Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classses, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Göttingen, Vol 1.

Pedersen, M. C. (2004). Gem and Ornamental Materials of Organic Orig.

Recommended websites

- https://www.cites.or

- ttp://www.conseildesventes.fr/sites/default/files/la_vente_de_cornes_de_rhinoceros.pdf

- http://www.conseildesventes.fr/sites/default/file/la_vente_de_cornes_de_rhinoceros.pdf

- http://www.iucnredlist.org/

- http://www.larousse.fr/encyclopedie/vie-sauvage/rhinoc%C3%A9ros/178163

- http://www.mbar.org/collections/borne%202/pages/asie/05/01.html

- http://news.mongabay.com/2014/10/the-inconvenient-solution-to-the-rhino-poaching-crisis/

- http://www.rhinoresourcecenter.com

© Marie Chabrol. This article was published in "Le Gemmologue" (2019).