Beads cut from gastropod mollusc shell disguised in a coral necklace

The GGTL-Laboratories in Geneva recently received a coral necklace for expertise.

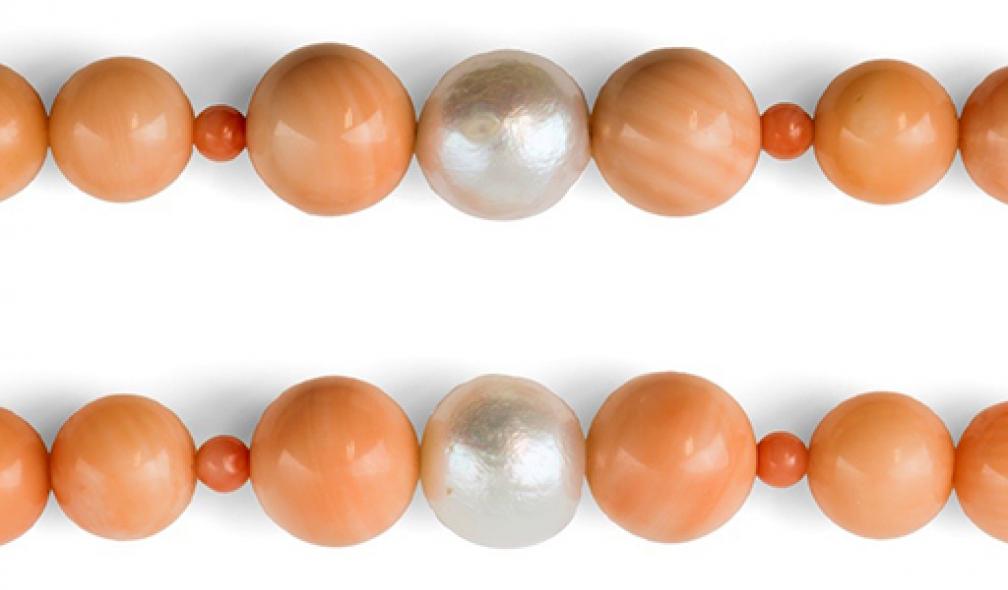

The necklace weighted 100.55 grams and contained 115 beads on its unique row: 8 round white freshwater cultured pearls and 107 beads, diameters between 3.3 and 10.2 mm, all showing the same "salmon" colour.

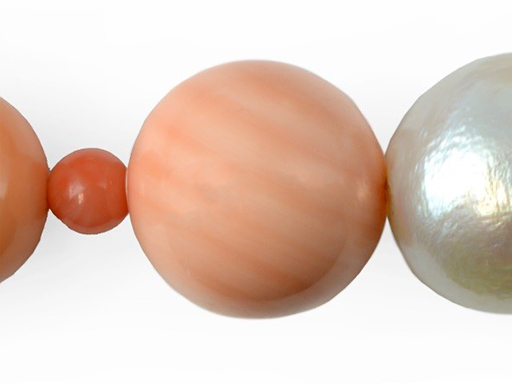

Observing the necklace under the microscope, the gemmologist identified mainly coral beads (here Corallium elatius, Ridley, 1882). Then after careful consideration, she noticed that on both sides of each freshwater cultured pearl was inserted a bead cut in a gastropod mollusc shell, obviously from a Strombus gigas (Linaeus, 1758) and not the coral bead as it would have seemed at first sight (figure 1). Indeed, pink and orange coral beads are occasionally mistaken for conch pearls (Farn, 1986, cited by Fritsch & Misiorowski, 1987).

Fig.1: White freshwater cultured pearl surrounded by two beads cut in a gastropod shell on both sides and smaller coral beads.

Mixing up pink or orangey coral and non-nacreous pearls can be efficient because they may have similar appearance as coral has a wide range of tint and saturation variation.

The identification to discriminate Strombus gigas from coral beads is made by structure observation and in some case by measurement of the weight per unit volume or the specific gravity (SG).

The Strombus gigas shells display a diagnostic flame-like structure (figure 2a), a characteristic arrangement we encounter in natural non-nacreous pearls from gastropods (Strombus gigas, Voluta melo, etc). This pattern is caused by the striated appearance of aragonite crystals that compose the inner layer of the shell (Campbell Pedersen, 2004). In the very best specimens, the “flames” can be identified by microscopic observation as thin lamellae that are almost parallel to one another and are sometimes perpendicular to the axis of pearl, thereby giving rise to rough chatoyant effect (Fritsch & Misiorowski, 1987).

We can distinguish them from polished coral beads which display banded striations that are much more regular than the flame structure seen on conch pearls and shells. The longitudinal ridges which are represented by the parallel striated pattern are spaced of 0.25 to 0.5 millimetres between the lines (Campbell Pedersen, 2004). In cross-section, these striations appear as radiating lines with very faint, concentric lines joining them, in a pattern somewhat resembling a spider’s web (figure 2b) also called tree ring structure (Campbell Pedersen, 2004). Coral also shows distinct surface pits.

Fig.2a: Flame-like structure in Strombus gigas pearl. The scale bar indicates 500mm.

Fig.2b: Typical spider web structure in coral. The scale bar indicates 500mm.

Note that the characteristic flame-like and the spider web patterns are not always present or directly seen in these materials. Not all the conch pearls exhibit their pattern without magnification: if the flame structure is not visible with the unaided eye, they are called porcelaneous (Fritsch & Misiorowski, 1987).

Depending on the location of the drilled hole, the spider web pattern may be invisible. Lack of the radial lines may indicate that it is a shell. A complete lack of structure is always alarming; the striations should be easily visible in red corals, but harder to discern in lighter coloured materials (Campbell Pedersen, 2004).

Another way to differentiate these materials is to measure the specific gravity. The precious coral SG is between 2.6 and 2.7 (Webster, 1983) and is strongly dependant on the porosity of the individual piece (Karampelas and al., 2009) whereas that of the pink conch pearl is around 2.85. This would correspond to a mixture of about 40% calcite (SG=2.71) and with 60% aragonite (SG=2.95) (Webster, 1975, cited by Fritsch & Misiorowski, 1987). It must be noted that this method may only be use as an indication because of the approximate results given by hydrostatic balance and because of concerned gems may cover almost the same range.

We can generally distinguish a bead cut in a shell from a non-nacreous natural pearl by only using a microscope: The beads cut in a shell display a layered structure with an uneven distribution of the flame-like pattern (figure 3) contrary to the flame-pattern uniformly visible in all directions in natural pearls (figure 2, left). The distribution of this particular pattern in beads cut from a shell is even more irregular than in natural pearls that have been reshaped.

Fig.3: A bead cut in a shell of Stombus gigas displaying a layered structure of different colours.

Thus, as it is demonstrated by this case, a microscopic examination must be systematically done on every single piece of pink coral necklace.

Authors

- Emilie Disner, GGTL Laboratories Switzerland. Website, ResearchGate, LinkedIn.

- Franck Notari, GGTL Laboratories Switzerland. ResearchGate, LinkedIn.

References

- Campbell Pedersen M., 2004, Gem and ornamental materials of organic origin. Elsevier Butterworth Heinemann, London, 151, 211-212.

- Farn A.E., 1986, Pearls : Natural, cultured and imitation. Butterworths, London.

- Fritsch E. & Misiorowski E., 1987, The history and gemology of queen conch « pearls ». Gems and Gemology, 23 (4), 208-221.

- Karampelas S., Fritsch E., Rondeau B., Andouche A. & Métivier B., 2009, Identification of endangered pink-to-red stylaster corals by raman spectroscopy. Gems and Gemology, 45 (1), 48-52.

- Webster R., 1975, Gems: Their sources, descriptions and identification, 3rd ed. Archon Books, Hamden, CT.

- Webster R., 1983, Gems: Their sources, descriptions and identification, 4th ed. Butterworth & Co., London, 562.

© The Gemmological Association of Great Britain. This article was published in "The Journal of Gemmology". (2015), Issue 42(7), pp 572-575.